The Freedom of the Common – a history of Langfield Common – Laurence Cockcroft

In 1953, when I was ten, I walked with my father across Langfield Common towards Holderstones, the huge rocks which look down on Withens Reservoir. As we approached the stones he lay down in the grass and gazed at the moor and the sky. I never saw him again in such a relaxed mood and so in touch with nature. That moment gave me an abiding love for the Common which has never left me. But its history is the story of struggle between those who wanted to graze their livestock on it, to quarry its stone and to capture its water for the Rochdale Canal and the mills of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The view across the Common from Holderstones to Stoodley Pike

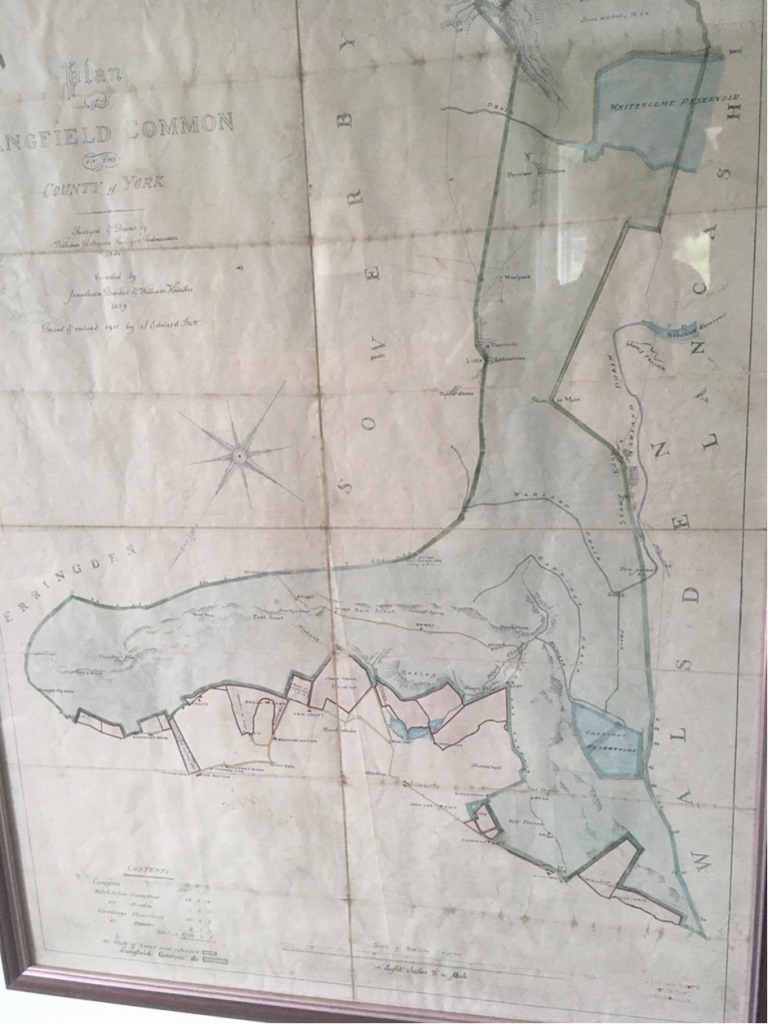

In its early history the Common just avoided being fenced in by the ‘palings’ erected by Earl John Warenne around 1330 to secure the family’s well-established hunting rights in this part of ‘Sowerbyshire’. But either by negotiation or defiance ‘Mankinholes Moor’, which the Common was then called, was left outside the fence as it was used by farmers working the strip farms of Mankinholes to graze their livestock, although a rent was nonetheless paid to the Earl Warenne family of 26/- per year (about £1,300 in today’s money). Warenne transferred the moor to William of Langfield and, through a marriage settlement, it subsequently passed to the Hamerton family who did not live locally but sided with the ‘Pilgrimage of Grace’, opposing Henry VIII’s Reformation and in 1537, Sir Richard Hamerton, was executed. As a result, the ownership of the common then reverted to the Crown until the Civil War of 1642 to 1651 when it was bought by Sir Gervais Clifton who was a Royalist and in political disfavour after the war and who quickly sold it to four local yeomen for £150 (£27,000 in 2020 money). These four were the core of the ‘Freeholders’ whose prime interest was for livestock grazing on the moor by then registered as about 1800 acres. To avoid over grazing this had to be controlled and 304 ‘gates’ (allowing 1 head of cattle per gate) were issued, a number which has not varied over time since 1671. We don’t know whether this allocation was based on usage or payment, but they are now integral to property ownership rights though some have been transferred between Freeholders. The current list is kept for legal purposes by Calderdale Council.

For most of the next 200 years the Common remained a shared grazing ground of significant value to those with ‘gates’, and most of the farmhouses built in the Langfield area (such as Kilnhurst) held ‘gates’, sometimes buying land from the Freeholders. There were constant struggles over both ‘encroachment’ for building and for overgrazing. Borders were challenged: along what is now the Pennine Way there is a stone with the engraving “This Common doth Belong to the Freeholders”, obviously confirming the Freeholders’ rights. By 1705 a ‘pinder’ or herdsman had been appointed to control livestock numbers and the Freeholders brought numerous court cases against unlawful graziers. After a formal peace in the Napoleonic wars in 1814, land was allocated to a group of five Trustees (who were also Freemasons) to construct a ‘pike’ at Stoodley to celebrate the peace. Although delayed by Napoleon’s return to fight at Waterloo, it was completed by 1816, only to fall down, apparently struck by lightning, when the Crimean War broke out in 1853. Working with the Freemasons, the Freeholders were active in the rebuilding and financing the new Pike in stone in 1856, a magnificent legacy to the region.

This bold re-commitment was captured by J. Barnes, a local poet, whose final verse of a longer poem reads :

Yet like the fabled Phoenix, thou

From out thy ashes rose –

Thy friends were firmer, greater, now,

Than had been all thy foes ;

Again they raised thy heavenward sign –

And may it long remain,

A Monument of Peace benign,

On Langfield’s moorland plain .By the late eighteenth century, the real potential of the Common as a source of water, first for the Rochdale Canal and then for the five water-powered mills of Lumbutts stream, had been recognised. The Rochdale Canal Company built Whiteholme Reservoir (close to Blackstone Edge) in 1833 and Gaddings Dam West at about the same time, only to find that the expanding millowners of Lumbutts (the Fieldens, the Uttleys and the Greenwoods) objected to their uptake of water and the company was obliged by the courts to fund the construction of a second dam (Gaddings East) for the exclusive benefit of the millowners. (Gaddings West is the one which is now known nationally as a centre for ‘wild swimming’). The Fieldens were increasingly active in the management of the moor and were represented in all the Freeholders’ meetings, generally held at the Dog and Partridge (now the Top Brink). In 1881 John Fielden of Dobroyd (one of the sons of John Fielden, MP) was granted permission to build the New Withens Road, from the Shepherd’s Rest to Withens Gate on the packhorse trail down to Withens (he was particularly interested in the shooting rights). Other subscribers intended to link this road to the Pike but this was never fulfilled.

The new dams and the huge expansion of Todmorden from 1800 onwards required very large quantities of stone. Langfield Common was one of the principal sites for quarrying, and by 1844 there were five quarries on the north-facing slopes of the moor, all of which were rented by quarrymen for both a fixed fee and a royalty on the number of cut stones. By 1840 the ‘illegal getting of stone’ had become an issue and several illegitimate quarry men were brought to court.

But the Common has another history of protest. David Hartley (“King of the Cragg Vale Coiners”) was executed at York in 1770 for an alleged association with the murderers of the magistrate who had been investigating his network of counterfeiters. Nonetheless in the same year his name was carved very prominently on Holderstone Rocks by one or more of his associates. The Basin Stone (strictly speaking just outside the Common boundary), on one of the pathways from the Shepherd’s Rest to Gaddings, was frequently used for meetings of public protest – captured by Alfred Bayes in his painting of a Chartist meeting there in the 1840s (which he had apparently attended as a boy). Billy Holt, author and artist, called a meeting to found a new religion there on a cold December morning in 1923, as recounted in his book ‘I Haven’t Unpacked’. We will never know the real origins of the ‘Two Lads’ – large cairns which look down on Withens: I was always told that they were erected in memory of two Walsden boys, caught in a storm searching for seagulls eggs after the construction of the reservoirs. If so, it’s a tribute to the sensitivity of generations of walkers that they remain very much intact.

Today, the Common continues to be managed by the Freeholders (now numbering the 45 who retain gates) who agree grazing and shooting rights. Since 2010 the Common has been awarded an Environmental Stewardship Scheme, funded by DEFRA, which has targeted the restoration of peat bogs (by gully blocking) and the planting of sphagnum moss – both to increase the retention of carbon – and some replanting of heather. A second key objective is an increase in the bird population. It seems likely that this support will be extended under DEFRA environmental grants scheduled for 2024.

It would be nice to think that the hundreds of swimmers who trek up to Gaddings every year would be aware of this grand heritage and be more responsible in avoiding their residue of litter. The Chartists who met at Basin Stone, and the boys commemorated at Two Lads, would be shocked by their legacy.

August 2021

FLCockcroft@gmail.com

Laurence Cockcroft is a Freeholder of Langfield Common but writes in his individual capacity